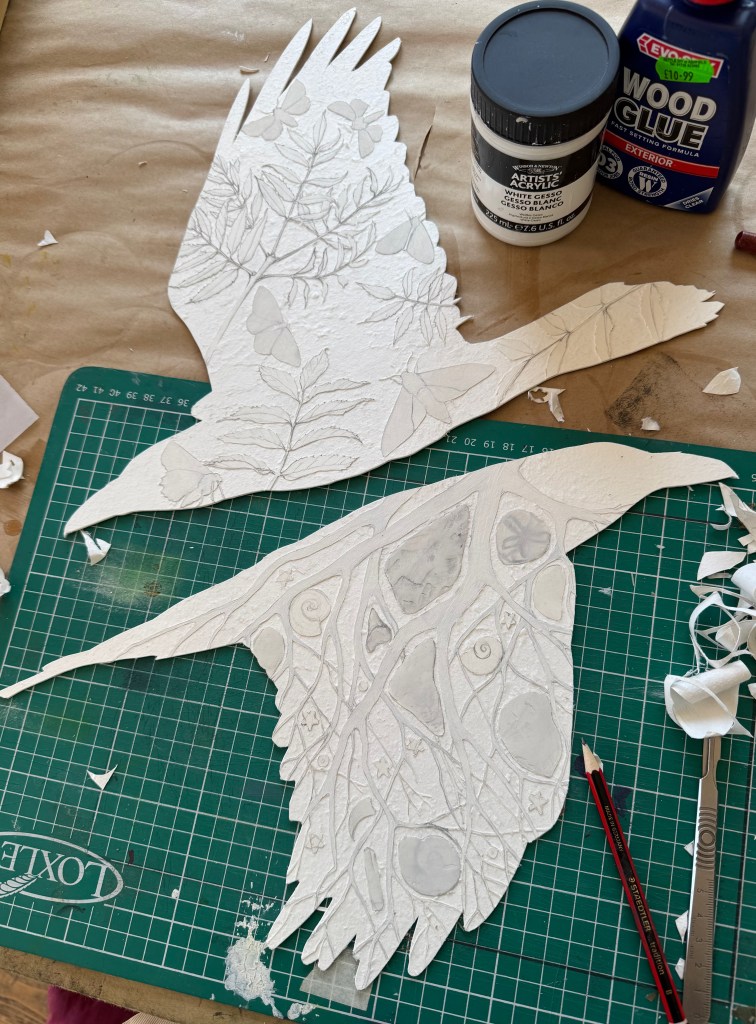

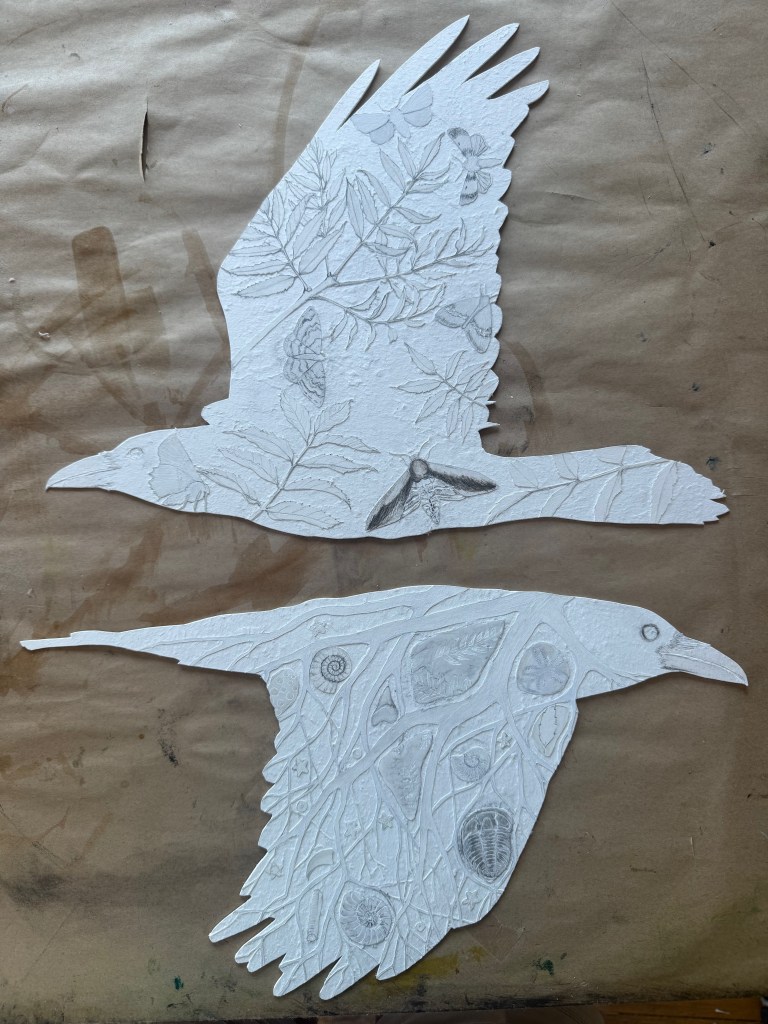

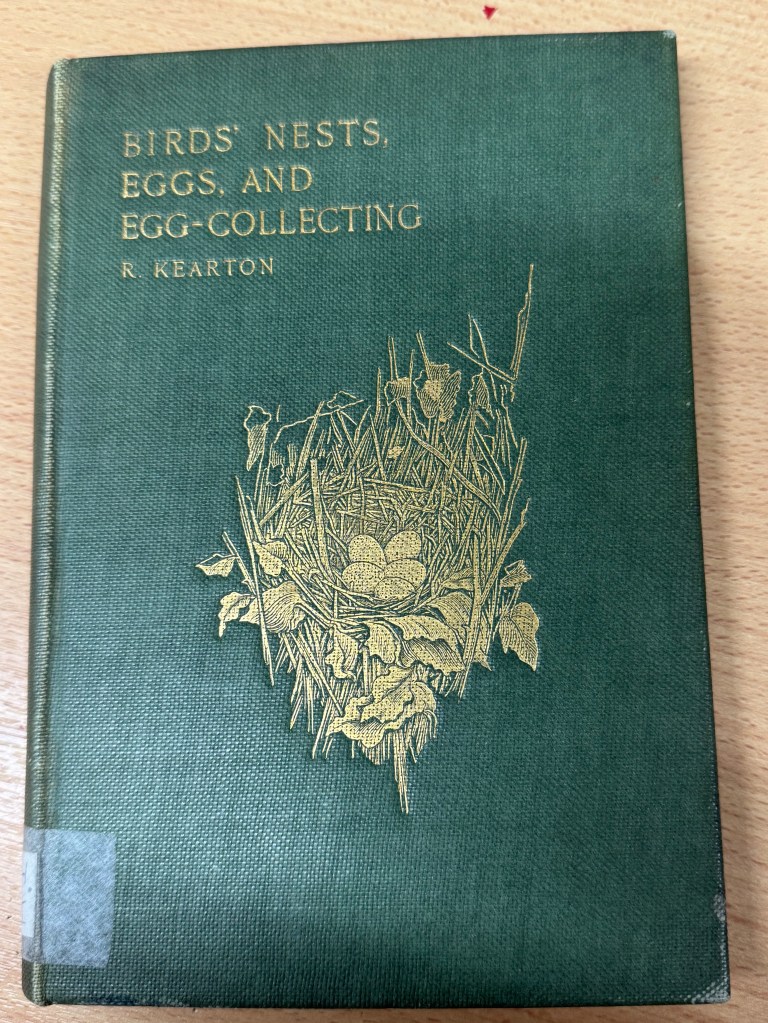

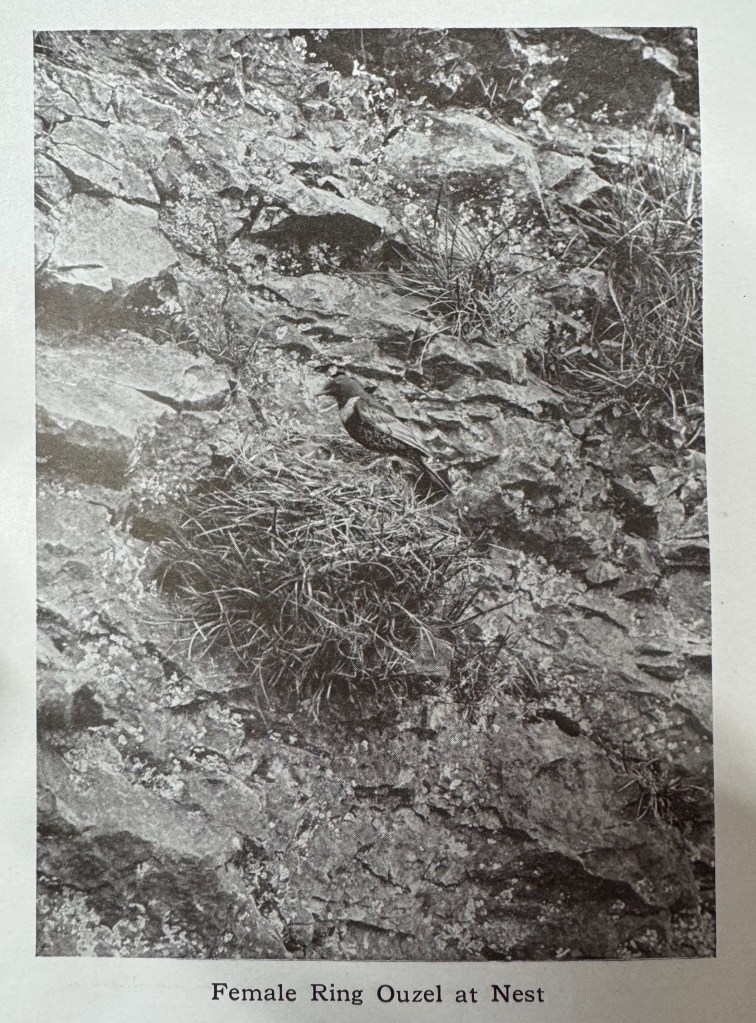

Yesterday I spent a happy few hours in the archive at the Dales Countryside Museum (DCM). I’m carrying out research for Cherish which explores the history and celebrates priority species birds in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. I’m looking back at various books and accounts where the authors talk about their experiences of birds in the dales and I started with the diaries of Marie Hartley and continued to the books of Richard Kearton (1862-1928) (illustrated with his brother Cherry’s (1871-1940) gorgeous monochrome photographs).

Richard and Cherry Kearton were naturalists and pioneers of nature photography. They were born and brought up in the Yorkshire Dales at Thwaite in Swaledale. For more information about their fascinating lives see this blog HERE

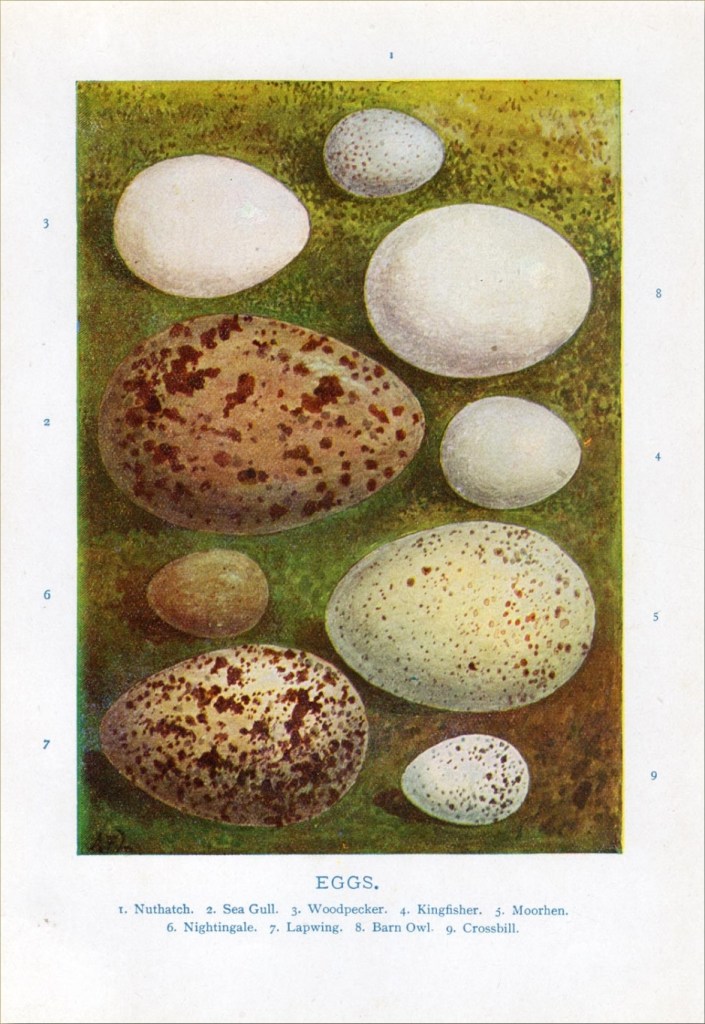

I began by looking at Birds’ Nests, Eggs and Egg Collecting which was published in 1890 and revised in 1896. Richard says “this book is not intended to encourage the useless collecting of birds’ eggs from a mere bric-à-brac motive, but to aid the youthful naturalist in the study of one of the most interesting phases of birdlife” and he goes on to share his ideas and philosophical approach to studying birds and their reproductive behaviour. In it he provides guidance on the subject of egg collecting and preserving and provides information about the nesting behaviour and eggs of individual species . He states that he hopes “that the Act of Parliament empowering County Councils to protect either the eggs of certain birds, or all birds breeding within a given area, will be of great benefit to our feathered friends”.

Egg collecting was a regular past-time for naturalists during the nineteenth and early twentieth century and many children growing up in the Yorkshire Dales in the 1940s and 1950s may well have spent time doing so too. With this pastime often came the kind of general knowledge of nature and the landscape that has been lost amongst many of our current generation which is why I am encouraged by the recent successful campaign to instate a nationwide Natural History GSCE in schools.

The Protection of Birds Act 1954 made egg collecting generally illegal but there was also an earlier bill, The Protection of Lapwings Bill 1928, that I find particularly interesting. Lapwings are one of my selected birds for this project and I am very fortunate to see them fairly regularly. At one time they were abundant across the country, so much so that their eggs were taken in the thousands to sell as a culinary delight in London. In his book At Home With Wild Nature published in 1922, Richard Kearton says “I wish some epicure would try a boiled rook’s egg for breakfast and proclaim from the house-tops of Belgravia its superiority over that of the plover or lapwing. It would be a great boon to the latter bird, which is being slowly but surely exterminated, to the detriment of the farmer in particular, and the public in general”.

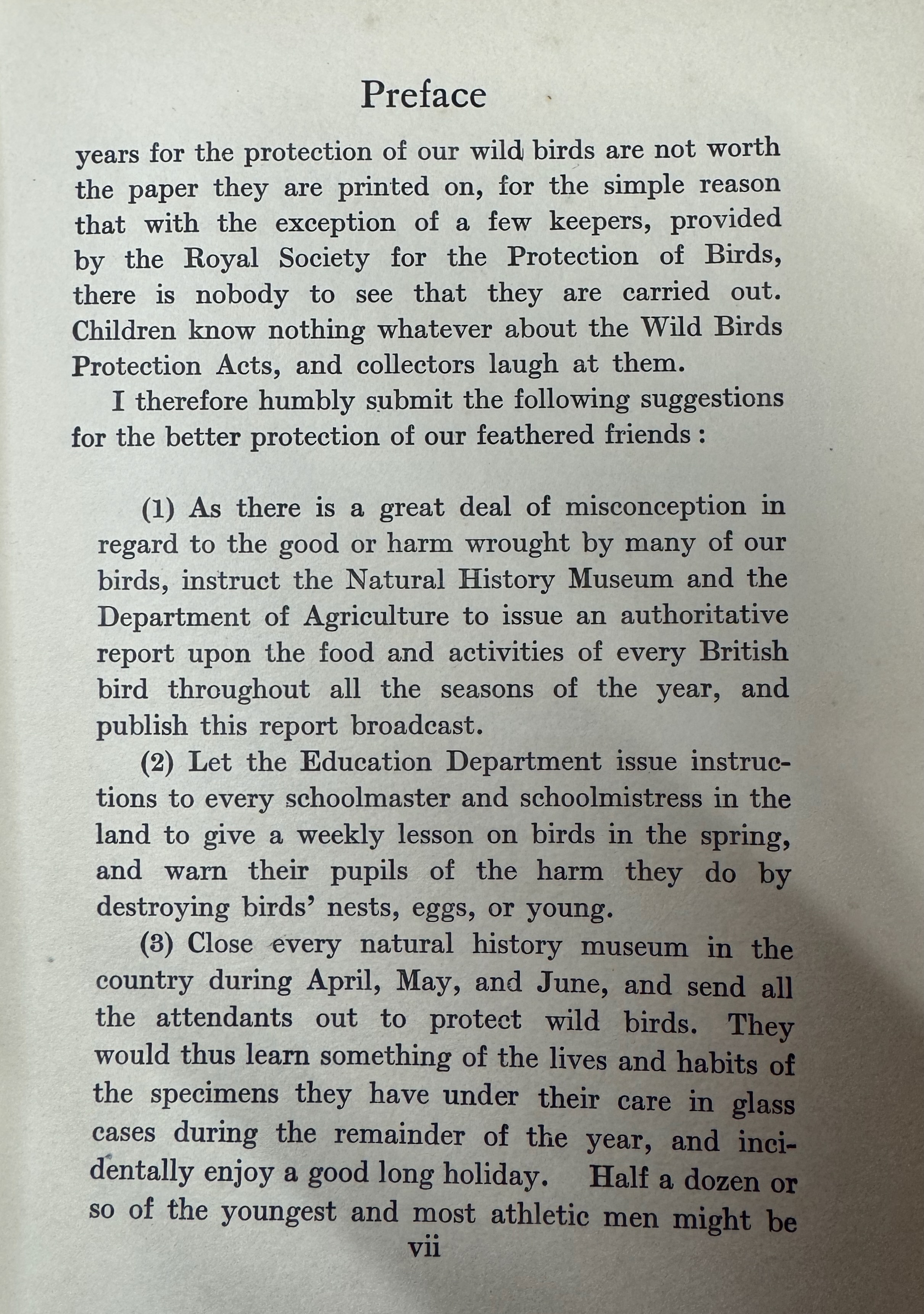

Kearton goes on to say “I have been an observer of bird life all my days, but never remember a time when members of the avian world were so purposefully persecuted as the present. It is no exaggeration to say that not quite ninety per cent of the nests, great and small, built in places accessible to public are wantonly destroyed”. He outlines his proposals to help protect birds in the preface of the book (see photos above).

I also read his thoughts on the rise in sheep farming and how he connected it to the decrease in the number of lapwings, wheatears and other moorland birds. I found a passage in which he also talks about “game-preserving” being a “disastrous business” to hen harriers. Coupled with the recent news of the successful prosecution of a game keeper who killed a hen harrier near Grassington, it is poignant that over a century later we are still encountering the same problems but they are now compounded by other threats to wildlife such as the rise in human populations and tourism, changes in agricultural practises and climate change.

There’s a lot to do in order to help our precious wildlife which is why one of the highlights of 2025 for me was my participation in the Northern Curlew Skill Share event organised by Matthew Trevelyan of Nidderdale Natural Landscape. This brought together land owners, farmers, ecologists, artists, writers, poets (to name but a few interested parties) who shared the common goal of trying to pool resources and skills to help find ways to conserve the endangered Curlew. It reminded me of how it isn’t all ‘doom and gloom’ and that I can play a small part by raising awareness via my work. The YDNPA’s Nature Recovery Plan “sets out the Biodiversity Forum‘s aspirations for action between now and 2040, aiming to conserve and enhance the biodiversity within the National Park” and this, combined with the efforts of many individuals and groups across the Yorkshire Dales gives rise to hope that we can make a difference.

Should anybody reading this blog have their own memories of birds in the Yorkshire Dales that they would like to share, please do feel free to comment below or send me a message through my website HERE. I’d love to hear them.