One of the pieces that I’ve made for my exhibition, ‘The View From the Fells: In the Footsteps of Marie Hartley’, is a continuation of a passion of mine that began a few years ago. Upland meadows are a wonderful feature of the Yorkshire Dales and people travel miles to see them during the months of late May and June and haymaking (or ‘haytime’ as it is known around here) is something that Ella Pontefract and Marie Hartley talked about a lot in their books. I have written a post all about the meadows at Muker HERE Unfortunately, across the country we have lost the majority of our haymeadows due to changes and intensification in agriculture but many landowners, farmers and conservationists are now working together to try to protect and conserve those that remain having recognised the ecological, cultural, agricultural and aesthetic value of them. I’ve been fortunate to live close to a pair of meadows that I have been observing for six years now and the incredible diversity of plant species, and the insects and birds that feed on them, continues to surprise and delight me.

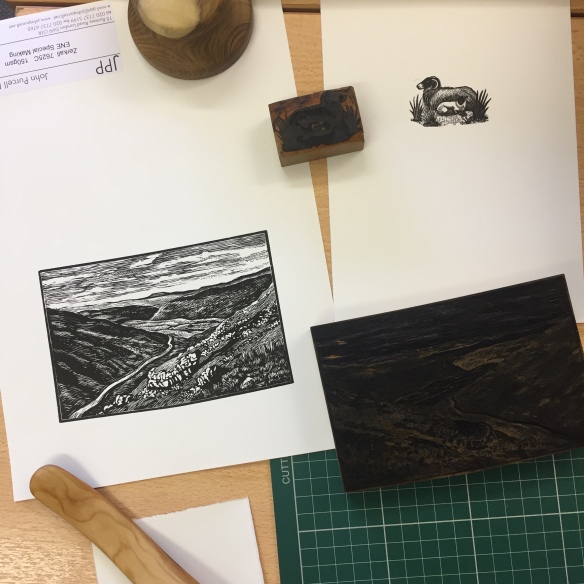

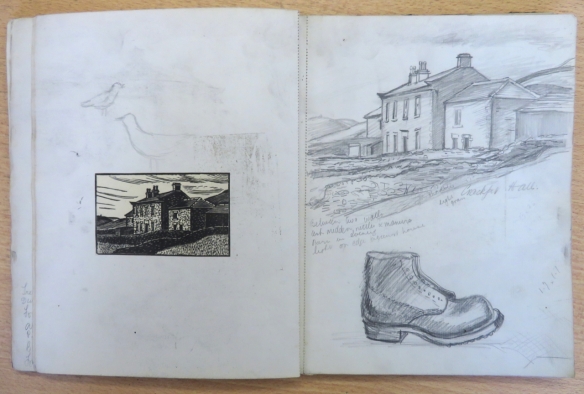

In 2017 I created a large-scale print installation in a field barn which celebrated our upland hay meadows (see my blog post HERE). For my exhibition at the Dales Countryside Museum, I have gone to the other extreme and created a series of 95 miniature printing plates that form one larger piece. I wanted to reflect the colours and the myriad of plants and insects that can be found in just a small area of a traditional hay meadow. I have also been fascinated by the fact that Marie Hartley worked on such a small scale to create the wood engravings that illustrated the three Dales books and I wanted to try working on a similar scale myself. Going from 4 metre long printed hangings to tiny plates of often no more than 2.4 x 4cm was a challenge but also really enjoyable.

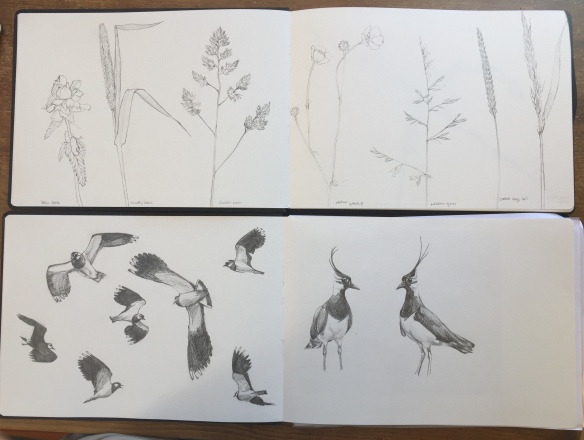

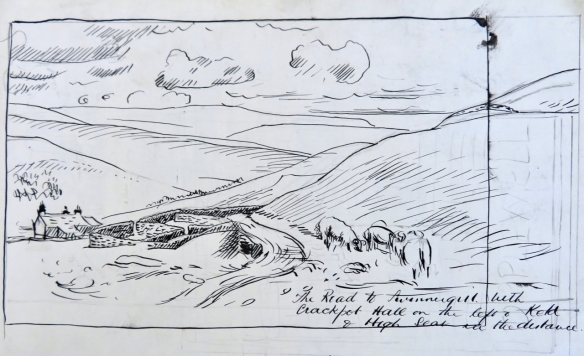

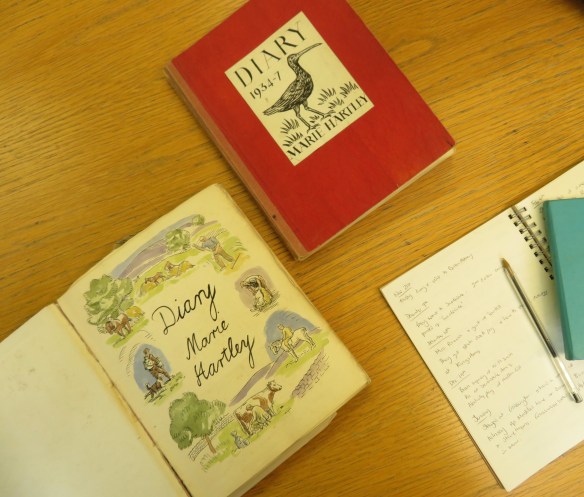

My meadow collection has been a long time in the making. I began the work last year when the hay meadows were in full flower. I spent time sketching the different grasses and flowers in preparation for making the plates. It became obvious that the piece would be something of a labour of love and I was tied up with other work last year so I put it to one side until January when I knew I’d have six months to work almost exclusively on the final work for the exhibition. The finished piece is created within an old print type drawer of the kind that you often see in junk and second hand shops. I’ve used smaller ones before in my Collections project and I like the way they give the pieces a museum quality with each print becoming an artefact within each space. I also thought that each individual print shown in a section of the tray would give the whole piece a feeling of a cross section of a meadow and there was a connection with Marie Hartley and her wood engraving blocks and the original books being created using letterpress.

My meadow collection has been a long time in the making. I began the work last year when the hay meadows were in full flower. I spent time sketching the different grasses and flowers in preparation for making the plates. It became obvious that the piece would be something of a labour of love and I was tied up with other work last year so I put it to one side until January when I knew I’d have six months to work almost exclusively on the final work for the exhibition. The finished piece is created within an old print type drawer of the kind that you often see in junk and second hand shops. I’ve used smaller ones before in my Collections project and I like the way they give the pieces a museum quality with each print becoming an artefact within each space. I also thought that each individual print shown in a section of the tray would give the whole piece a feeling of a cross section of a meadow and there was a connection with Marie Hartley and her wood engraving blocks and the original books being created using letterpress.

I coded all the sections of the tray and then drew out rectangles in my sketchbook that related to each section. My aim was to try to depict all the plants that are typical of a healthy upland meadow and I also included a number of invertebrate species such as bees, moths, butterflies and beetles. These are attracted to the different species and in turn become food for birds and animals and so the whole habitat becomes a vital ecosystem. I set about making every drawing into a small cardboard collagraph plate using cutting and painting techniques. It was very fiddly and has made me realise how much my eyesight has deteriorated in my forties. Fortunately, I found that without my contact lenses I could see really well close up so I worked like that most of the time and then blundered round my studio looking for my glasses whenever I needed to see beyond my nose!

At the end of February I went to Ålgården Studios in Sweden for a fortnight of intensive work and I made sure that I finished making all of the meadow plates before I left. It had turned into almost a month’s work and I was paranoid about the plates getting damaged or lost so I stored them all in a wooden box in our house. I returned on 12th March just as COVID-19 was getting serious and printing the plates was the first thing that I did as we went into lock down. This situation has tested everyone and everyone’s experience of it will be different but I know I’m not alone in having gone through a period of anxiety, lack of motivation and difficulty in concentrating. Creativity is a strange beast and I find that I need very specific circumstances for me to feel inspired and motivated to make things and so I was very happy to have a box of 95 small plates to print. It was something that needed doing in order to complete the piece but all of the thinking and creative part had pretty much been done and now I just had to go through the time consuming practical part of inking, wiping and printing each one. I spent the next week and half doing just that whilst listening to audio books (thank you Ann Cleeves!) and podcasts. Do listen to ‘The Poet Laureate has gone to his Shed’ if you want to hear some excellent conversations between Simon Armitage and various creative people. (NB. I was once part of a group of fellrunners who helped Simon find his way off of Cross Fell and arranged for him to give a poetry reading in Dufton. He gave me his Mars bar…I’ve eaten it!).

Each printing plate is inked and wiped à la poupée which meant that I first inked them in sepia and then I wiped back the plant part of the plate with cotton buds and carefully applied the colours before then very carefully wiping again so that the colour was just a hint. The paper I printed onto was dampened and blotted so it was nice and soft and I printed groups up together with plenty of space for cutting to size. I used my etching press in order to get enough pressure to push the paper into all the details of each plate.

The prints were then left to dry. Using my dad’s old workmate and a table saw, I measured and cut a small block of MDF to fit each section of the tray. I’m notoriously accident prone and so it was slightly scary cutting with a spinning blade but I soon got the hang of it (with safety glasses and big gloves) and when all the blocks were cut, I painted the surface with gesso and then glued the prints in place using bookbinders glue so that they would be archival and last for many years. I then waxed the surface of each print with an acrylic wax to protect them before fitting them into place. The finished result was exactly what I was hoping for and I am pretty happy with it. Due to the huge amount of work involved, I’ve decided that I need to make it a small edition of ten in order to make it cost effective and so that I can keep one for future shows. I will make up two trays and then the others will be made to order. I’m now back to making more conventional collagraph prints for the exhibition and will talk more about some of those in a future post.

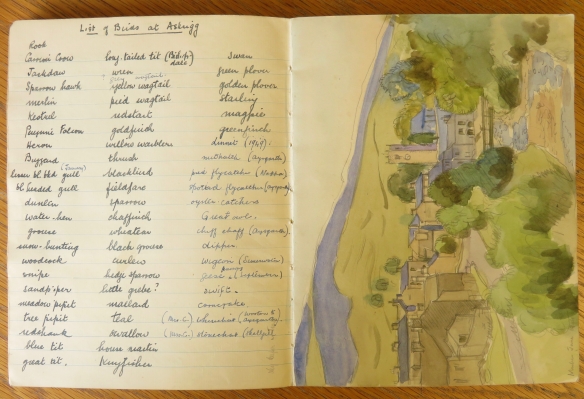

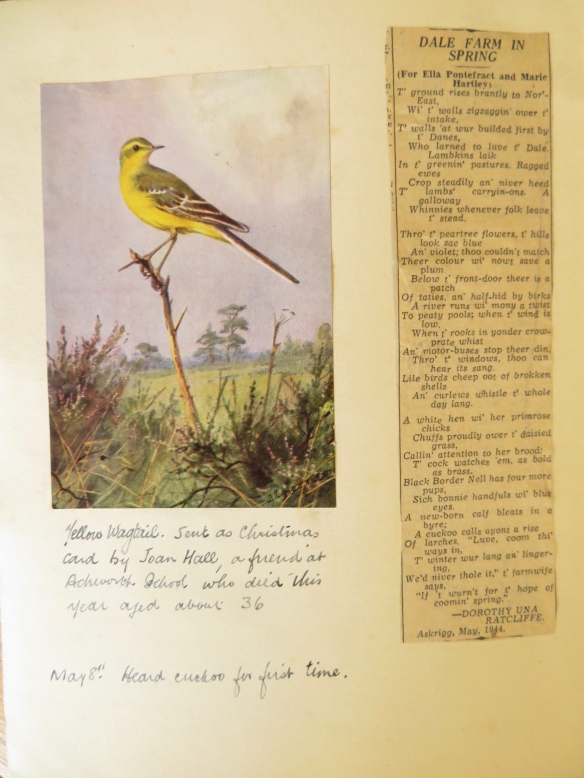

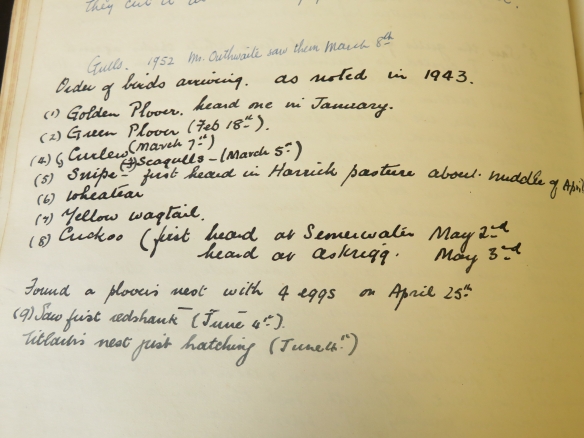

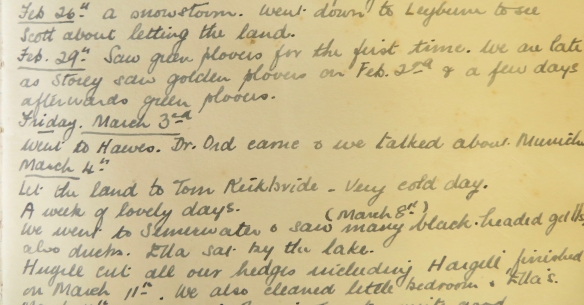

I think that one of the most poignant things is the fact that she refers to seeing corncrakes near Askrigg and these have now vanished from the Yorkshire Dales. I’ve been out and about and seen some really amazing wildlife. Here are some collages of photos taken on my visits to Muker, Keld, Penyghent, Plover Hill and Semerwater.

I think that one of the most poignant things is the fact that she refers to seeing corncrakes near Askrigg and these have now vanished from the Yorkshire Dales. I’ve been out and about and seen some really amazing wildlife. Here are some collages of photos taken on my visits to Muker, Keld, Penyghent, Plover Hill and Semerwater.