Ravens have captivated me for most of my life and I am fortunate to live in an area where I see them often. When I summit Ingleborough there will invariably be a pair flying around and I see them when I am running over Plover Hill and Pen-y-ghent. These intelligent members of the corvid (crow) family are also the largest and the ones that feature most in the folklore and mythology of cultures from all over the world. (Below are just a few photos I’ve taken over the years, note the difference in size between the raven and the crow in the last photo!).

For Charms and Murmurings at Ryedale Folk Museum – my latest Collections exhibition with Josie Beszant & Charlotte Morrison – we are showing work inspired by the folklore, mythology and stories surrounding birds. Ravens feature in many of our pieces including our collaborative work ‘Corvid’. I made a template showing the primary and secondary wing feathers of a raven and we each made fourteen feathers that, when collected together, formed a pair of ‘wings’. I love the distinctive primaries on a raven’s wing that look like fingers stroking the sky.

(l-r: Charlotte, Josie, me)

My collagraph feathers are inspired by the many places throughout Yorkshire that are named after ravens and also the Norse myth of Odin and his two ravens, Huginn & Muninn (Charlotte’s feathers are ceramic and Josie’s are paper collages).

Ravens are carrion eaters and, because of this, they were often associated with death and loss. They are also ‘talking birds’ that are able to mimic human speech and this is thought to be the reason that they appear as messengers in so many myths, often travelling between worlds, to bring news to their human companions. Back in 2000, I created a raven collagraph inspired by Celtic mythology and called The Messenger:

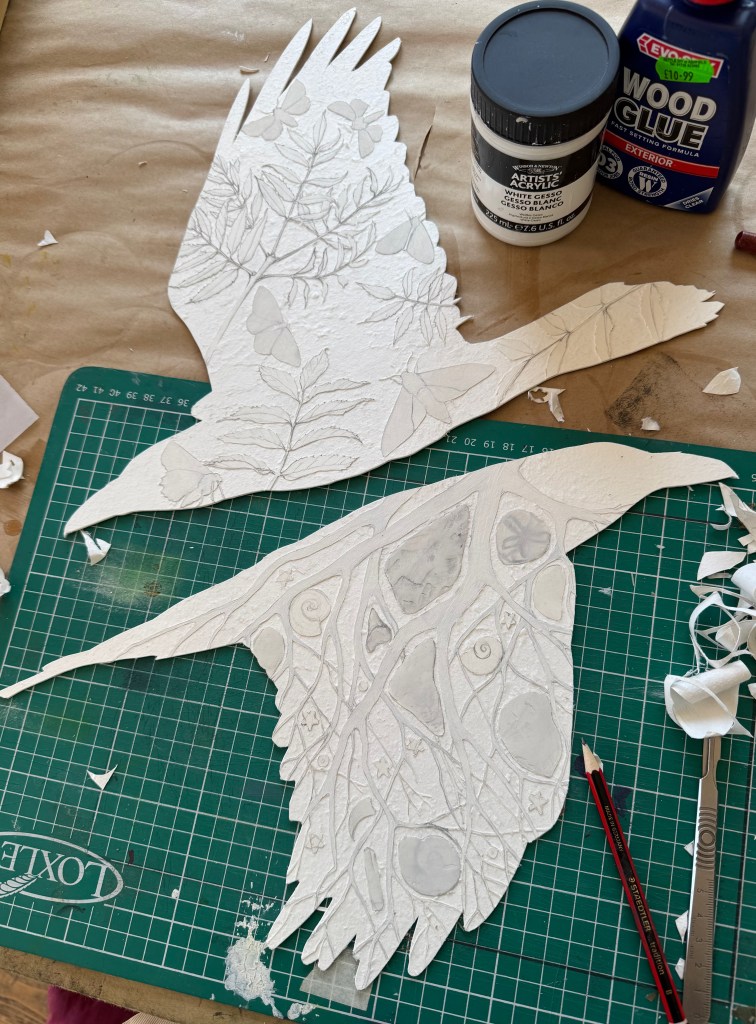

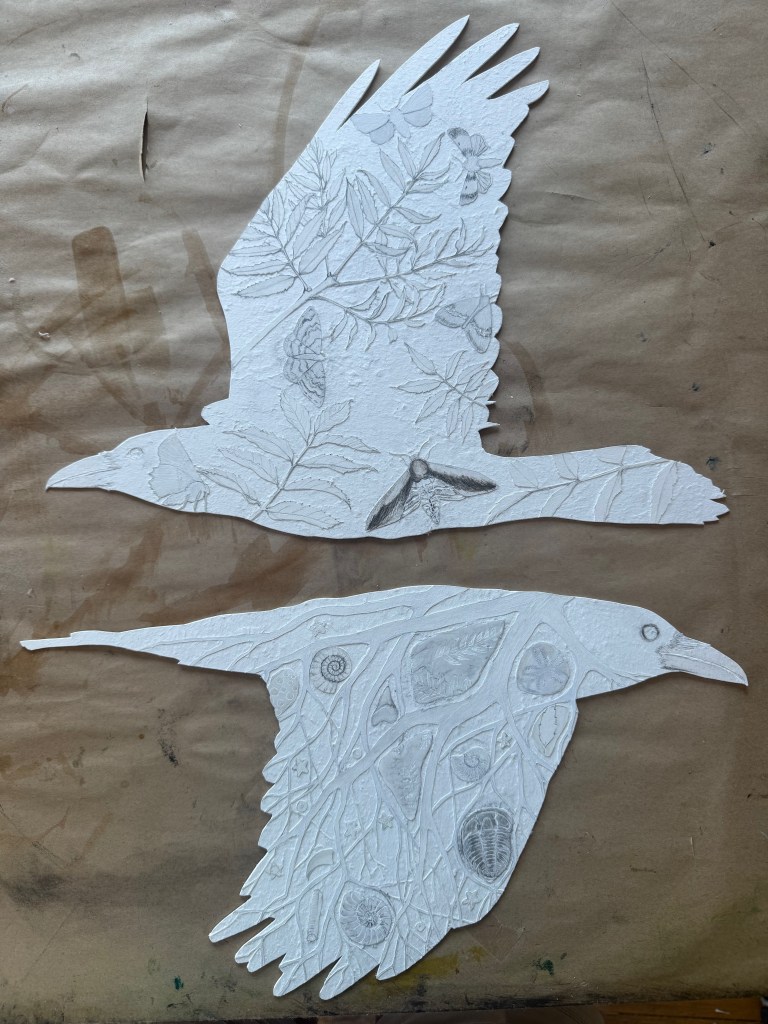

25 years later(!) I have chosen to explore the story of Odin’s ravens and for Charms and Murmurings I have created this piece entitled Thought and Memory:

Huginn (Thought) and Muninn (Mind or Memory) would sit beside Odin – often regarded as the God of Ravens, the dead and warfare – and each morning he sent them out across the world and they would report back on everything they saw and heard. The names of the ravens are difficult to translate but Huginn is thought to represent the intellect/comprehension/perception and Muninn the emotions/memory/urges (to put it very simply). Whilst researching ravens, I came across an article that referenced a quote from the Poetic Edda called Grímnismál (in old Icelandic):

Huginn ok Muninn fljúga hverjan dag Jormungrund yfir;

óumk ek of Hugin, at hann aptr né komit, pó sjámk meirr um Munin.

A translation of this is:

Thought and Memory fly every day the whole world over;

each day I fear that Thought may not return, yet I fear more for Memory.

This really resonated with me and, coming at the idea from an ecological viewpoint, I wanted to depict Thought (Huginn) as living in the natural world that we see and experience physically and I have used the branches of an ash tree which directly links to the sacred ash tree (Yggdrasil) in Norse myth. I’ve created moths to fly among the branches symbolising thoughts and the spirit.

For Memory (Muninn), I depicted the roots of an ash tree with fossils caught amongst them representing the past, our memories and the underworld realm of the dead. The fact that Odin was an elderly man and that he feared losing Muninn more than Huginn made me think about the devastating disease of dementia. Losing our cognitive ability and short-term memories, we become lost in our own world unable to make sense of the here and now and often become physically lost both to our families and friends but also in reality when we can’t find the associations needed to navigate in the world around us. I am not really sure how this collagraph relates to my thoughts but I made it with them whirring around in the background.

NB some people believe that Huginn and Muninn were linked to Odin himself and that through shamanic practices he would send his own thought and mind journeying across the world. Ravens have often been a bird that humans and mythic beings were thought to transform into.

As is usual with my work, there are layers of thought behind it and some I won’t be able to verbalise for a while (there is something about ‘ash dieback’ in there I think!). I often create my prints from ideas that are more instinctive and come from experiences that link to things I feel but haven’t found a way to express in words. This is why I love to meet people at art fairs and discuss my work with them. At the Saltaire Inspired Winter Makers Fair last weekend, I had some wonderful discussions about my new work and found that visitors were providing insights that made me feel like shouting ‘yes, yes, that’s it!’.

Finally, this last piece is part of my ‘animal, vegetable, mineral’ series that takes my feather collection as inspiration and links to manmade objects and the plant world. Here I have created collagraphs of a raven feather, a sprig of bog myrtle (sweet gale) and a piece of Viking hack silver which is actually from a former project. Bog Myrtle is thought to be a plant that the vikings used to create a drink which helped them ‘berserk’ before going into battle! There is an interesting article about the varied uses of the plant HERE.

Thank you to everyone that has visited the exhibition and for all of your feedback. I welcome your ideas and experiences about birds, folklore and my work so please do feel free to comment below.

Charms and Murmurings is on at Ryedale Folk Museum until 2nd November.

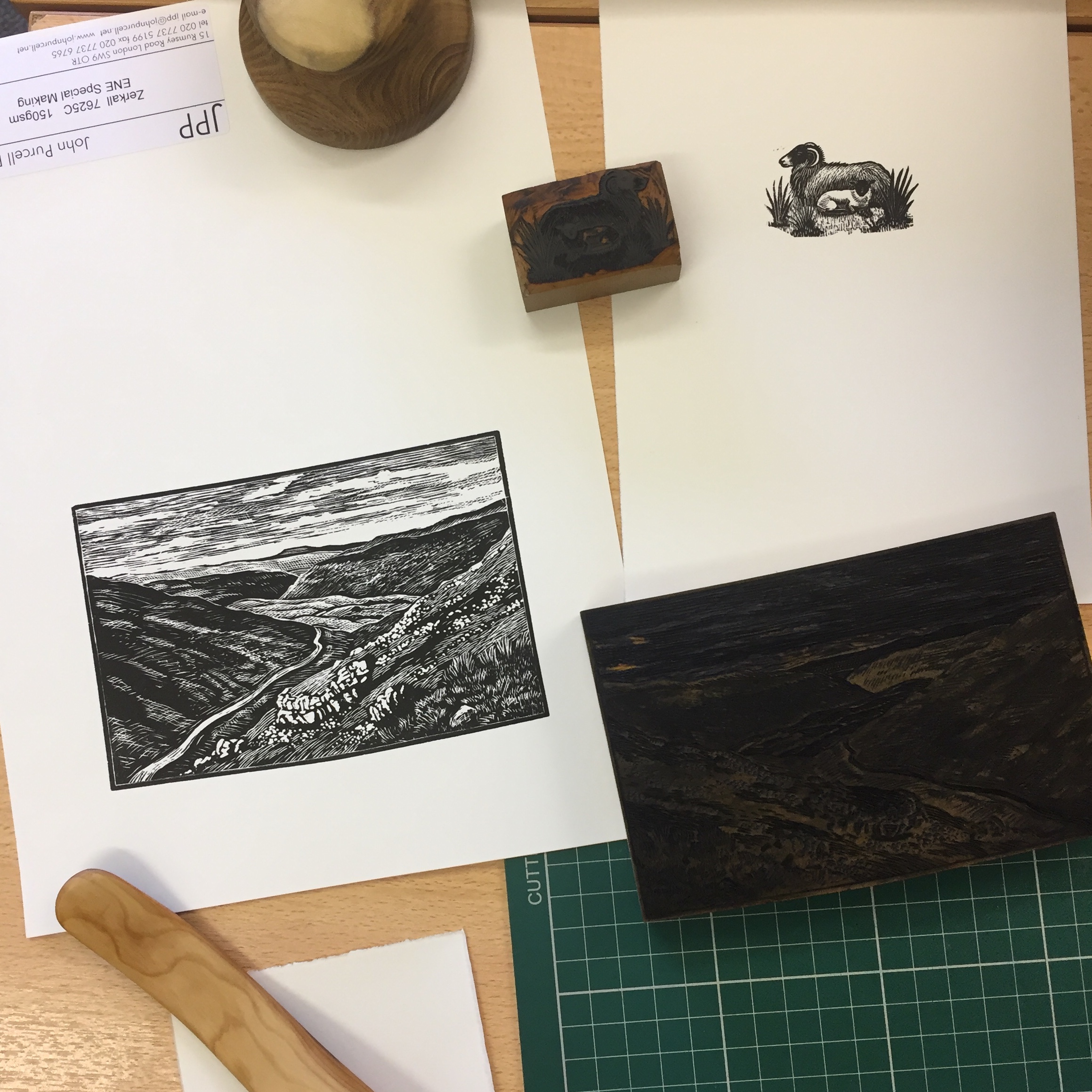

As with all of my work, I started with an idea and that developed and changed as I made various decisions about what to include, where to focus and how to physically create the work. I selected 14 birds from Marie’s list that were either red or amber status. I decided to create an individual printing plate for each with her actual list reproduced in the middle. As I started to work out the overall design, I thought about whether I’d label the birds or not and once I decided that I would, I realised that the plates were starting to resemble the old cigarette cards that people used to collect. I have a few John Players ‘Bird of the British Isles’ cards and I love the size and detail of them. I made each little collagraph card using cutting techniques combined with gesso, acrylic medium & wood glue for texture. The labels were made by reversing text on my computer, printing it out, varnishing it and scratching the letters out to create areas of drypoint. I used a font that resembled letterpress type from the 40s.

As with all of my work, I started with an idea and that developed and changed as I made various decisions about what to include, where to focus and how to physically create the work. I selected 14 birds from Marie’s list that were either red or amber status. I decided to create an individual printing plate for each with her actual list reproduced in the middle. As I started to work out the overall design, I thought about whether I’d label the birds or not and once I decided that I would, I realised that the plates were starting to resemble the old cigarette cards that people used to collect. I have a few John Players ‘Bird of the British Isles’ cards and I love the size and detail of them. I made each little collagraph card using cutting techniques combined with gesso, acrylic medium & wood glue for texture. The labels were made by reversing text on my computer, printing it out, varnishing it and scratching the letters out to create areas of drypoint. I used a font that resembled letterpress type from the 40s.

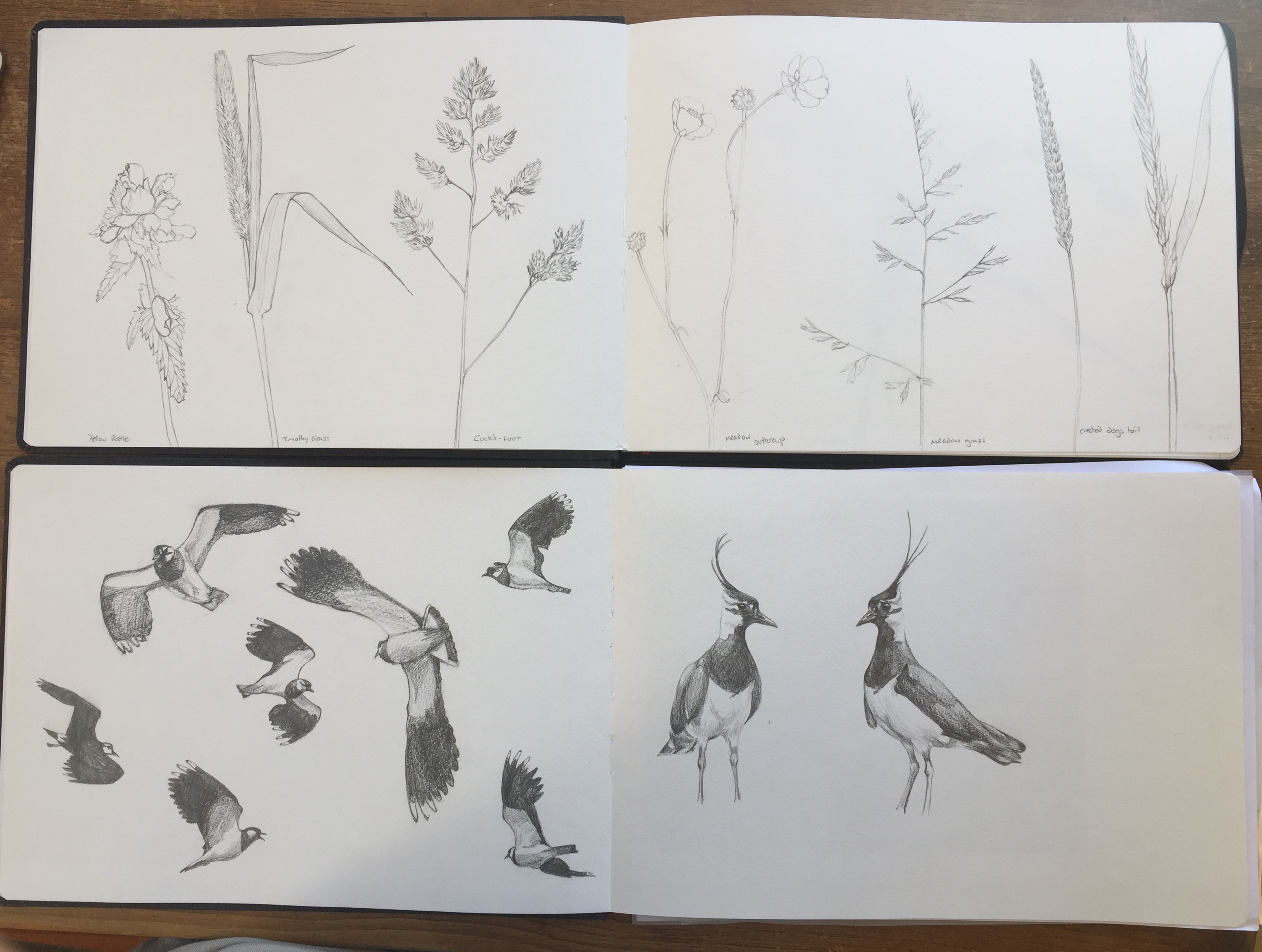

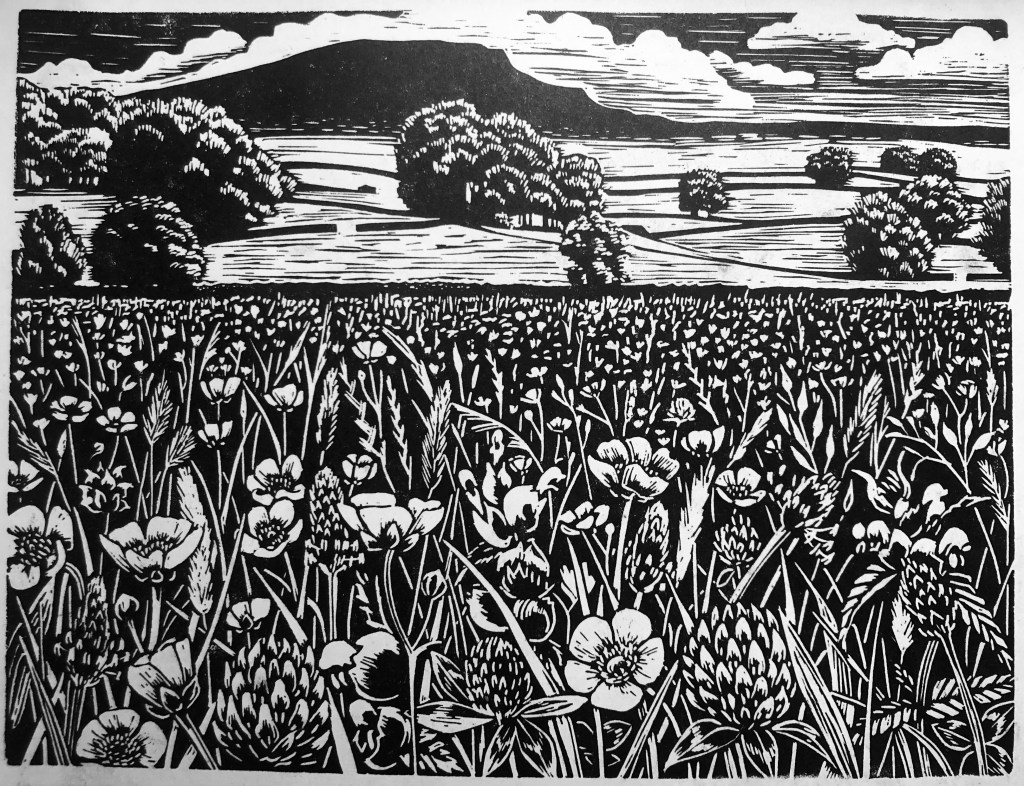

My meadow collection has been a long time in the making. I began the work last year when the hay meadows were in full flower. I spent time sketching the different grasses and flowers in preparation for making the plates. It became obvious that the piece would be something of a labour of love and I was tied up with other work last year so I put it to one side until January when I knew I’d have six months to work almost exclusively on the final work for the exhibition. The finished piece is created within an old print type drawer of the kind that you often see in junk and second hand shops. I’ve used smaller ones before in my Collections project and I like the way they give the pieces a museum quality with each print becoming an artefact within each space. I also thought that each individual print shown in a section of the tray would give the whole piece a feeling of a cross section of a meadow and there was a connection with Marie Hartley and her wood engraving blocks and the original books being created using letterpress.

My meadow collection has been a long time in the making. I began the work last year when the hay meadows were in full flower. I spent time sketching the different grasses and flowers in preparation for making the plates. It became obvious that the piece would be something of a labour of love and I was tied up with other work last year so I put it to one side until January when I knew I’d have six months to work almost exclusively on the final work for the exhibition. The finished piece is created within an old print type drawer of the kind that you often see in junk and second hand shops. I’ve used smaller ones before in my Collections project and I like the way they give the pieces a museum quality with each print becoming an artefact within each space. I also thought that each individual print shown in a section of the tray would give the whole piece a feeling of a cross section of a meadow and there was a connection with Marie Hartley and her wood engraving blocks and the original books being created using letterpress.

I think that one of the most poignant things is the fact that she refers to seeing corncrakes near Askrigg and these have now vanished from the Yorkshire Dales. I’ve been out and about and seen some really amazing wildlife. Here are some collages of photos taken on my visits to Muker, Keld, Penyghent, Plover Hill and Semerwater.

I think that one of the most poignant things is the fact that she refers to seeing corncrakes near Askrigg and these have now vanished from the Yorkshire Dales. I’ve been out and about and seen some really amazing wildlife. Here are some collages of photos taken on my visits to Muker, Keld, Penyghent, Plover Hill and Semerwater.